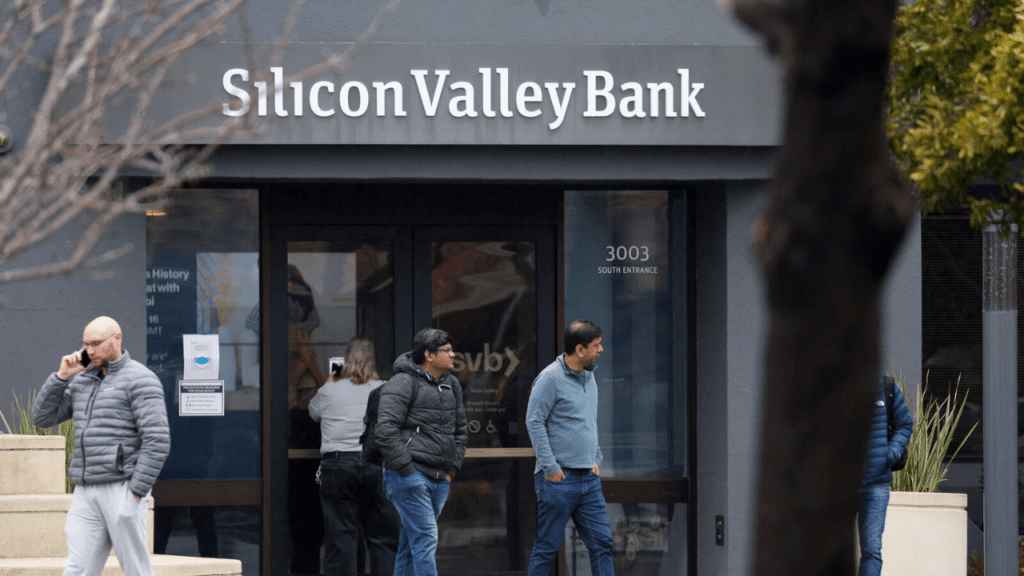

One of the most important lenders in the world of technology start-ups failed on Friday because of bad decisions and worried customers. The federal government had to step in to help.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation said on Friday that it would take over the Santa Clara, California-based Silicon Valley Bank, which has been around for 40 years. The bank’s failure is the second biggest in U.S. history and the biggest since the financial crisis of 2008.

The move gave the regulator control over nearly $175 billion in customer deposits. Even though the quick fall of the 16th largest bank in the country brought back memories of the global financial panic of a decade and a half ago, it did not immediately cause people to worry that the financial industry or the global economy would be ruined in a big way.

Silicon Valley Bank failed two days after its emergency moves to handle withdrawal requests and a sudden drop in the value of its investments shocked Wall Street and depositors, sending its stock tumbling. A person with knowledge of the talks said that the bank, which had $209 billion in assets at the end of 2022, had been working with financial advisers until Friday morning to find a buyer.

Even though Silicon Valley Bank’s problems are unique, a financial contagion seemed to spread to other parts of the banking sector. This led Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to reassure investors in public that the banking system was strong.

Investors sold the stocks of Silicon Valley Bank’s competitors, such as First Republic, Signature Bank, and Western Alliance. Many of these banks work with start-ups and have similar investment portfolios, so their stocks were dumped by investors.

During the day, trading in the shares of at least five banks was stopped several times because their sharp drops hit limits on the stock exchanges.

Some of the biggest banks in the country, on the other hand, seemed to be less affected by the fallout. Shares of JPMorgan, Wells Fargo, and Citigroup were all mostly flat on Friday after falling on Thursday.

That’s because the world in which the biggest banks work is very different. Their requirements for capital are stricter, and they have a much bigger pool of deposits than banks like Silicon Valley, which don’t have a lot of retail customers. Regulators have also tried to keep big banks from focusing too much on one area of business, and they have mostly stayed away from riskier assets like cryptocurrencies.

Sheila Bair, the former head of the F.D.I.C., said, “I don’t think this is a problem for the big banks. That’s the good news; they have a lot of different kinds of business.” Ms. Bair also said that the largest banks should have a lot of cash on hand because they are required to hold cash equivalents even against the safest forms of government debt.

A statement from the Treasury Department says that Ms. Yellen met with banking regulators on Friday to talk about the problems with Silicon Valley Bank.

Representatives from the Federal Reserve and the F.D.I.C. also met with members of Congress for a bipartisan briefing. This meeting was set up by Maxine Waters, a Democrat from California and the ranking member of the House Financial Services Committee.

This week, Silicon Valley Bank’s problems got much worse very quickly, but they have been getting worse for more than a year. Since it opened in 1983, the bank has been a go-to lender for new businesses and their leaders.

Even though the bank said it was a “partner for the innovation economy,” this moment came about because of some very old-fashioned decisions.

Silicon Valley Bank did what all banks do with the money it got from high-flying start-ups that raised a lot of money from venture capitalists: it kept some of the deposits on hand and invested the rest in the hopes of getting a return. When interest rates were low, the bank put a lot of customer deposits into long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage bonds, which promised small, steady returns.

That had been good for a long time. In 2018, the bank had $49 billion in deposits. By the end of 2020, they had $102 billion. One year later, in 2021, it had $189.2 billion in its bank accounts. During the pandemic, start-ups and tech companies had made a lot of money.

But it bought a lot of bonds right before the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates a little more than a year ago, and then it didn’t plan for the possibility that interest rates could go up very quickly. As rates went up, these investments became less appealing because the interest on newer government bonds was higher.

That might not have mattered as long as the bank’s customers didn’t ask for their money back. But because the flow of start-up funding slowed and interest rates went up at the same time, the bank’s customers started taking out more of their money.

Silicon Valley Bank had to sell some of its investments to get the money to pay off these redemption requests. On Wednesday, the bank made a surprise announcement that it had lost almost $2 billion when it was almost forced to sell some of its holdings.

It’s the classic Jimmy Stewart problem,” Ms. Bair said, referring to the movie “It’s a Wonderful Life,” in which Stewart played a banker trying to stop a bank run. “If everyone takes out money at the same time, the bank will have to start selling some of its assets to get the money back to the depositors.”

Investors started to worry about some of the regional banks because of these fears. Signature Bank is also a lender that works with new businesses, just like Silicon Valley Bank. It may be best known for its ties to the family of former President Donald J. Trump.

First Republic Bank, which is based in San Francisco and focuses on wealth management and private banking for high net worth clients in the tech industry, recently said that rising interest rates are making it harder for it to make money. Western Alliance Bank, which is also in the wealth management business and is based in Phoenix, is going through the same things.

Another bank, Silvergate, announced on Wednesday that it was closing down and going out of business because it had lost a lot of money in the cryptocurrency industry.

When asked for a comment, a First Republic spokesman sent over a filing the bank made with the Securities and Exchange Commission on Friday, which said that the bank’s deposit base was “strong and very well diversified” and that its “liquidity position remains very strong.”

A spokeswoman for Western Alliance pointed to a news release from the bank on Friday that talked about the bank’s balance sheet. The statement said that deposits are still strong. “Asset quality remains excellent.”

Signature and Silicon Valley Bank didn’t have anything to say about it. Representatives from the Federal Reserve and the F.D.I.C. did not want to say anything.

Some banking experts said on Friday that a big bank like Silicon Valley Bank might have been able to handle its interest rate risks better if President Trump hadn’t rolled back parts of the Dodd-Frank financial regulations that were put in place after the 2008 financial crisis.

In 2018, Mr. Trump signed a bill that made it easier for many regional banks to do business. Greg Becker, the CEO of Silicon Valley Bank, was a big fan of the change. It got rid of the requirement that banks with less than $250 billion in assets go through stress tests by the Fed and changed the amount of cash they had to keep on their balance sheets to protect against shocks.

A Fed spokesperson said Friday that Mr. Becker was no longer on the board of directors for the San Francisco Fed.

At the end of 2016, Silicon Valley Bank owned $45 billion worth of things. By the end of 2020, it had gone up to more than $115 billion.

The chaos on Friday made uncomfortable comparisons to the financial crisis in 2008. Small banks fail all the time, but the last time a bank this big fell apart was in 2008, when the FDIC took over Washington Mutual.

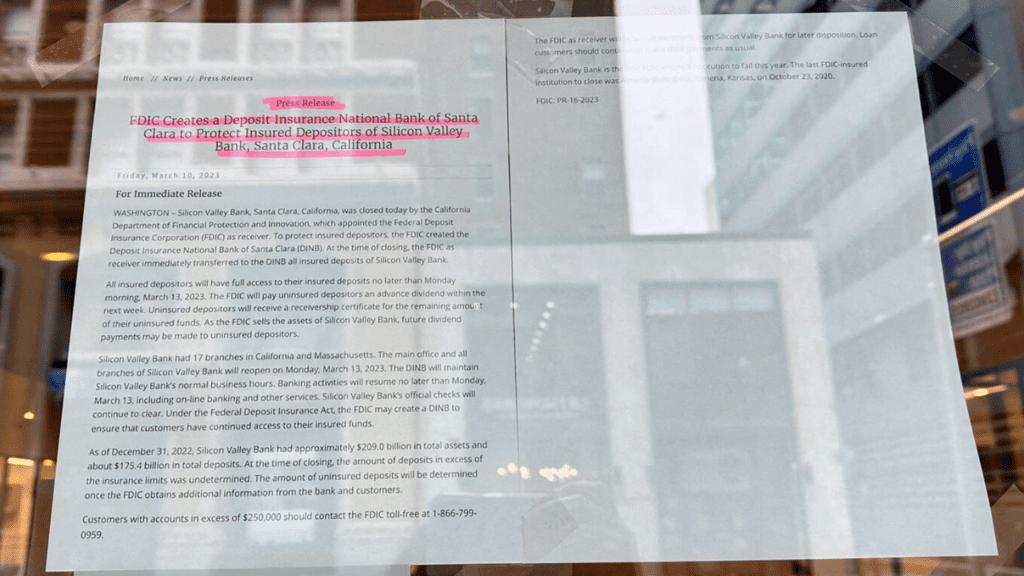

The F.D.I.C. rarely takes over banks when the markets are open. Instead, it prefers to put a failing institution into receivership on Friday, after business has ended for the weekend. But in the first few hours of trading on Friday, the banking regulator sent out a news release saying that it had created the National Bank of Santa Clara to hold the deposits and other assets of the failed bank.

The government agency said that the new business would be up and running by Monday and that checks written by the old bank would still clear. Customers with deposits of up to $250,000, which is the most the FDIC will cover, will get their money back, but there’s no guarantee that people with more money in their accounts will get it all back.

These customers will be given certificates for their uninsured funds, which means they will be among the first to be paid back with recovered funds while the FDIC has Silicon Valley Bank in receivership, though they might not get all of their money back.

When the California bank IndyMac failed in July 2008, there was no one to buy it right away, just like with Silicon Valley Bank. The FDIC put IndyMac in receivership until March 2009, and big depositors only got back half of their uninsured money in the end. When JPMorgan Chase bought Washington Mutual, account holders got their money back.

More Article.

Comments are closed.