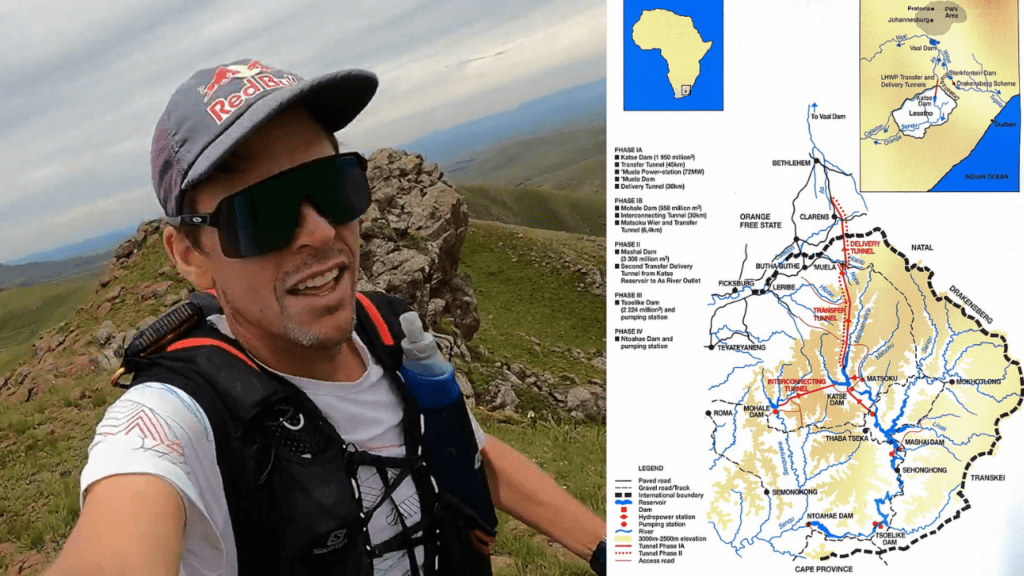

Ryan Sandes, a well-known ultra-athlete, was recently interviewed by CNN in his Cape Town home. He didn’t look tired at all. Until he took off his shoes, you wouldn’t know he had just come back from a 16-day run along the mostly unexplored mountains of Lesotho’s borders.

For runners, blisters and cracked feet are just part of the deal. For Sandes and his running partner Ryno Griesel, who created and finished Navigate Lesotho on April 27, they’re almost a source of pride. In 16 days, 16 hours, and 56 minutes, they went 1,100 kilometers (684 miles) and climbed more than 33,000 meters in elevation. They did this in very bad weather.

“In some ways, it was our toughest challenge,” Sandes told CNN. “But I think our maturity and the bond we have made it a lot easier because of what we’ve learned in the past.”

The two South Africans are used to going on dangerous trips. Together, they have the record for the fastest known time (FKT) on the Great Himalaya Trail in Nepal, which is one of the hardest routes in the world. They did it in 25 days and covered 1,504 kilometers (934.5 miles). They also hold the FKT on the famous Drakensberg Grand Traverse in their home country, beating the old record by 18 hours.

Even when Covid-19 was locked down in South Africa, Sandes ran a 100-mile ultramarathon around his house, which took him 26 hours to finish.

“He had gone about 87 miles (140 kilometers) and said, ‘I can’t go any further, this is the hardest thing I’ve ever done,'” says Vanessa Haywood, Sandes’s wife.

But going around the “Mountain Kingdom” of Africa would be even more difficult.

On foot in Lesotho

“Lesotho was definitely the most difficult in terms of conditions, but you don’t think of it that way because it’s so close to home,” Griesel said, adding that it’s a five-hour drive from Johannesburg.

It took two years to plan the trip, which Griesel compares to “building a puzzle.” During the pre-production phase, they mapped out places that didn’t have maps, got sponsors on board, made friends with locals, and checked out parts of the route they would later run.

“Most people say that getting started is the hardest part, which is true, and then the rest of the hard part starts,” he said.

Sandes says that they ran about a half-marathon each day, slogging through extremely cold, wet, windy, and muddy weather. Sandes and Griesel crossed a total of 187 rivers.

During the trip, temperatures changed from -5 degrees Celsius to 30 degrees Celsius.

Depending on the weather and their progress toward their 17-day goal, they slept some nights and didn’t sleep other nights.

Plan A had to be changed quite a few times, and Sandes said that they went back over some mountains and rivers and took different paths when the weather was bad.

A race in your head

Lesotho was also hard to get around mentally, but the two decided early on that they would not give up.

“When you’ve been freezing for two or three days, you can’t think straight because you haven’t slept, you’re very hungry, and you ran out of food two days ago, there are always 1,000 good reasons to quit,” Griesel said. “But once you take that off the table, you’re forced to keep moving toward the goal.”

They brought a lot in their packs, including clothes, food, water, extra socks, GPS trackers, water purification straws, headlamps, hiking sticks, sunscreen, and more.

And for fuel? Each runner brought a mix of whole foods and electrolyte mixes that were high in carbs, as well as one dehydrated meal per day. They think that they burned about 120,000 calories during the trip.

Griesel said that hot cross buns and chocolate were his favorite foods in Lesotho. “From a traditional point of view, I’ve always been really bad at diet,” he said. “But I do think that the best food is what you look forward to eating on these long projects.”

They weren’t completely alone on their expedition. A support crew on horseback, motorbikes, and four-by-fours helped resupply their basic needs and give them cooked food at different pre-planned locations.

Two peas in a pod

Sandes (age 40) and Griesel (age 42) met at the ultra-trail race Salomon SkyRun South Africa in 2012, where Sandes won and Griesel came in third. They ran the Drakensberg Grand Traverse together two years later and broke the FKT record.

“That’s where our friendship definitely began,” Sandes said. “Ryno and I are very different people, but I think we go well together.”

Sandes made a joke about how Griesel’s race stuff will be labeled and in order while his own is a mess.

“Even if I look at what we each bring to the table, I come from more of a running background and compete on the international circuit, while Ryno is more into adventure racing, and his mountain skills and navigation are next level,” he said.

Sandes is the strongest, and Griesel is the best at getting around.

“It’s fine to go fast as long as you go in the right direction,” Griesel said. “I think that’s where we really fit together.”

The humble runners are a good match for each other in more ways than just the skills they each have. Griesel said that Sandes is good at keeping morale up by enjoying the “mini milestones,” which helped him keep going during their run in Lesotho.

“We’d reach the top of a peak, and I’d say, ‘I still need 10 days to finish this,’ and he’d remind me where we’d started,” Griesel said.

Not going far from home

Even though these two will probably keep trying for FKTs, Sandes says that the pandemic has given him time to slow down and enjoy what his home continent has to offer.

“I’ve been lucky enough to run on all seven continents and see a lot of the world during my career,” he said. “But I feel like I haven’t seen enough of Africa.” “And I think that having to do more things close to home has made me love home even more.”

They also want to train the next generation of South African runners through programs like LIV2Run, which helps people from poor areas get ahead.

“In life, we all kind of need that connection to the outdoors,” said Sandes. “I think we’re so tied to technology that we need to break away from it so we can feel free, natural, and whole again.”

Comments are closed.