Many people in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, which has the largest open-air drug market on the East Coast, are fully addicted. They hunch over crates or stoops and openly sniff, smoke, or inject illegal drugs. Syringes are all over the streets, and urine stinks up the air.

The problems in the neighbourhood started in the early 1970s, when factories closed down and the drug trade took over. With every new wave of drugs, things are getting worse. Now that xylazine, a veterinary tranquillizer, is here, it’s adding more problems to a system that was already overworked.

Dave Malloy, a longtime social worker in Philadelphia who does mobile outreach in Kensington and around the city, said, “We need all hands on deck.”

Dealers are cutting fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is up to 50 times stronger than heroin, with xylazine, which is cheap and not controlled by the government. “Tranq” is the street name for xylazine, and “tranq dope” is fentanyl mixed with xylazine. When mixed with fentanyl or heroin, xylazine makes the high stronger and lasts longer.

But it’s also bad for your health: Because it cuts off blood flow to skin tissue, it can cause ulcers that won’t heal, called necrotic ulcers. Also, because xylazine is a sedative and not a narcotic, naloxone does not work as well to reverse the effects of an overdose of tranq dope as it does with other drugs.

The Drug Enforcement Administration says that xylazine has been spreading across the country for at least ten years. It started in the Northeast and moved south and west. Also, bad people overseas have found it easy to make, sell, and ship a lot of it. Eventually, it gets to the U.S., where it is often passed around by express delivery.

The first time xylazine was found in Philadelphia was in 2006. By 2021, it had been found in 90% of street opioid samples in the city. Statistics from the city show that xylazine was involved in 44% of all accidental fentanyl overdose deaths that year. The DEA says that there is no national data on xylazine-positive overdose deaths because testing methods during autopsies vary so much from state to state.

The results can be seen right here in Kensington. Users walk around with rotting wounds on their legs, arms, and hands that sometimes go all the way to the bone.

The drug xylazine causes blood vessels to narrow, which makes it hard to treat these ulcers. Dehydration and the fact that many users are homeless and don’t have clean places to live also make it hard to treat these ulcers, said Silvana Mazzella, associate executive officer of the public health nonprofit Prevention Point Philadelphia, which offers “harm reduction” services to help people with substance use disorders live safer lives.

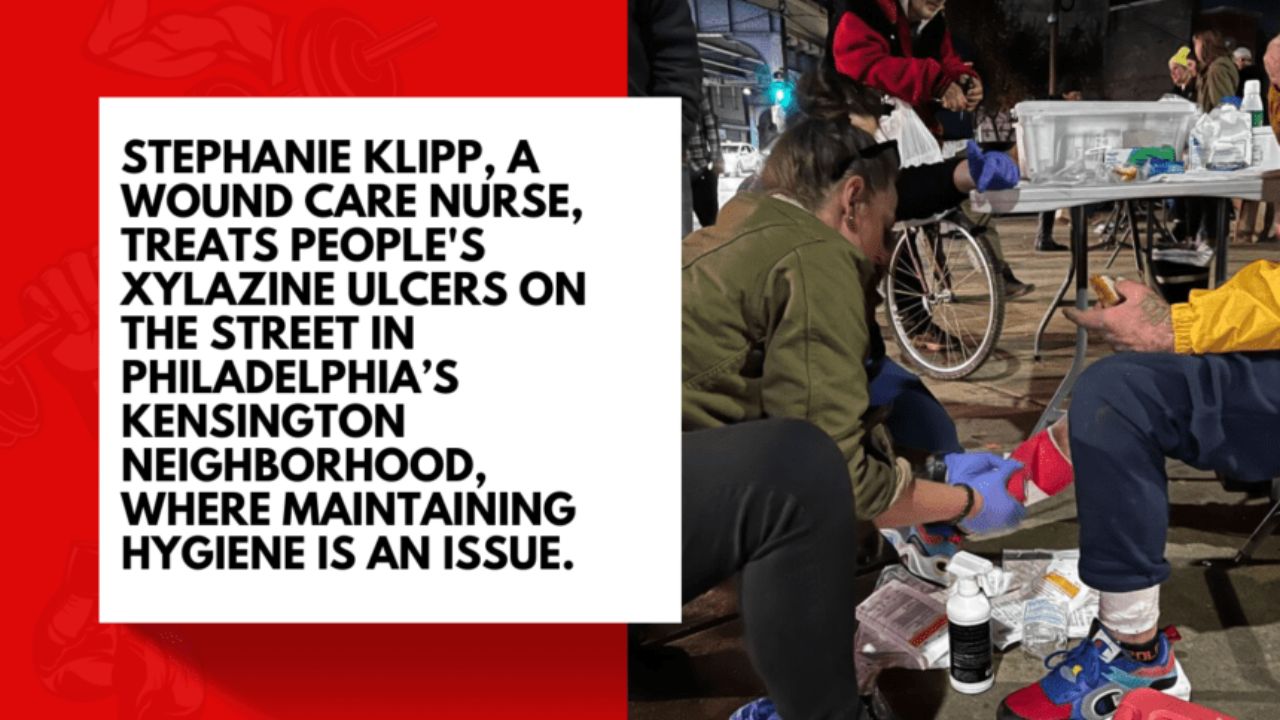

Stephanie Klipp, a nurse in Kensington who helps with these kinds of efforts and treats wounds, says she has seen people “living with what’s left of their limbs, with things that should have been cut off.”

Because xylazine is resistant to naloxone, the number of overdose deaths is going up. When a sedative stops someone from breathing, they need CPR and to be taken to the hospital so they can be put on a ventilator. Klipp said, “We have to keep people alive long enough to treat them, and that looks different here every day.”

When a person with tranq dope withdrawal gets to the hospital, it becomes important to deal with sudden withdrawal, which can be dangerous. There is little to no research on how xylazine works in people.

Melanie Beddis lived on and off the streets in Kensington for about five years because of her drug use. She remembers how hard it was to stop using heroin all at once. It was horrible, but after about three days of pain, chills, and throwing up, she could usually “keep food down and maybe sleep.” Beddis, who is now the director of programmes at Savage Sisters Recovery, said that Tranq dope raised the stakes. Savage Sisters Recovery offers housing, outreach, and other help to keep people who use drugs safe in Kensington.

She remembered that she couldn’t eat or sleep for about three weeks when she tried to stop using this mix in jail.

There is no clear formula for what helps people get off opiates and xylazine.

Dr. Jeanmarie Perrone, who started the Penn Medicine Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy, said, “We do need a recipe that works.”

Perrone said that she treats opioid withdrawal first, and if a patient is still uncomfortable, she often gives them clonidine, which is a blood pressure medicine that also helps reduce anxiety. Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant drug that is sometimes used to treat anxiety, has been tried by other doctors.

Methadone, which is used to treat opioid use disorder and can also be used to treat pain, seems to help people going through tranq dope withdrawal.

After a patient is stabilised in the hospital, xylazine wounds may be the most important thing to take care of. This can include everything from cleaning (called “debridement”) to antibiotic treatment (sometimes given intravenously for as long as a week) to amputation.

Philadelphia just said that it will start mobile wound care as part of its plan for how to spend the money from the opioid settlement. They hope this will help with the xylazine problem.

Klipp said that the best thing wound care specialists can do on the street is clean and bandage ulcers, give people supplies, tell people not to inject into wounds, and suggest that they get treatment in a medical setting. But many people get stuck in the cycle of addiction and give up.

Malloy thinks that it takes three or four hours for the effects of tranq dope to wear off, but it takes six to eight hours for heroin. He said, “It’s the main reason people don’t get the right medical care.” “They can’t stay in the ER long enough.”

Also, the ulcers that result are often very painful, but doctors don’t like to give people strong painkillers. “A lot of doctors see that as people trying to get medicine instead of trying to explain what’s going on,” Beddis said.

In the meantime, Jerry Daley, executive director of the local chapter of a grant programme run by the Office of National Drug Control Policy, said that health officials and law enforcement need to start cracking down on the xylazine supply chain and getting the message out that bad companies that make xylazine are “literally profiting off of people’s life and limb.”

This story was made by KHN (Kaiser Health News), a national newsroom that covers health issues in depth and is a big part of KFF’s operations (Kaiser Family Foundation). It was given permission to be used again.

Tags: Opioids, drugs, drug abuse, doctors, patients, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Comments are closed.